Presenting to you an engrossing interview with Professor Laurent GAYER

of SciencePo, Paris about his landmark book, “Karachi: Ordered Disorder and the

Struggle for the City (Hurst, 2014)”. This is an exclusive discussion where for

the first time the author addresses the Indian audience, presenting them the

secrets of the “City of Life!”

Karachi once got the reputation of being one of the most dangerous and

most violent cities on earth. Due to intense armed conflicts, the city often

was nicknamed, “The Beirut of South Asia” or “The Colombia of South Asia”. The

killings peaked at 2507 in the year 2013. Laurent confirmed that indeed

violence was central to the fabric of the city. However, it was also to some

extent contained, regulated. This was not a city on the verge of chaos or even

if it had at some point, it had been on the brink of a civil war, it never

really entirely fell into the abyss. It was indeed an enigma to understand why

the city was not more violent than it could have been. The author takes us

through his investigation to fathom the reasons behind what spared Karachi a

general conflagration despite repeated sequences of violent escalation accompanied

by ethnic, political and more recently religious polarization.

Further, Laurent unravels to us the root causes behind the rise and fall

of the Muhajir nationalism that was engineered and exploited by Karachi’s most formidable

political force, the “Muttahida Qaumi Movement (MQM)”. He also explores and

narrates the deep historical, cultural and emotional attachment that Muhajirs

have to their homeland, to their place of origin in India. Interestingly, many

colonies in Karachi still have names such as Delhi Colony, Bangalore Town,

Bihar colony, etc.

Laurent claims that the arrival to power of Narendra MODI in India has in a way rejuvenated both, the “Two Nation Theory” as well as the Pakistan nationalism. There is now at least a sense that Pakistan provided a roof and a certain limited, however imperfect protection to Muslims of the subcontinent.

Watch the interview as well to discover how poetry remains very much part of the everyday language of politics in Pakistan!

Notes:

1) Please note that there are simultaneous French and Hindi subtitles to

the interview.

2) Please consult the English transcript of this interview at the below

link.

3) Please consult the French transcript of this interview at the below

link.

4) Please consult the Hindi transcript of this interview at the below

link.

Anubandh: Hello! My name is Anubandh KATÉ. I am a Paris based engineer and today I have a great pleasure to invite and talk to Professor Laurent GAYER of SciencePo. Welcome Laurent!

Laurent: Thank you.

Anubandh: I do not know Laurent if you believe in this but often Parisians and French people call Paris as the center of the world. And I tend to agree with them. Because the kind of research work that is done here, on South Asia, including countries like India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka and others, I think it is incredible. Many people unfortunately, back in India and in Pakistan ignore this fact. We have of course Christophe JAFFRELOT who has written more than 24 books on India, 7 on Pakistan and you have collaborated with him. You have written books with him and you as well have written many books (yourself). Therefore, do you agree with this assertion that “Paris is the center of the world?”

Laurent: No, not really. I mean we are just bringing, trying to bring a little contribution. Nevertheless, obviously, most scholarship on India, on South Asia comes from the subcontinent itself. Moreover, we have drawn inspiration from generations of Indian historians, sociologists, political scientists, anthropologists. Now they are scattered also across the world, across the US in particular where increasingly their scholarship is being threatened. I think France has been, I mean, it has been playing its role. However, it is a marginal contribution in regard to the vast amount of scholarship on South Asia.

Anubandh: Nevertheless, I have a question regarding the

importance of Europeans writing on India - Pakistan and why it is

essential and different. We will get into that a bit later but to present you

formally. You work at the CNRS which is « Center National de La Recherche

Scientifique » (National Center for Scientific Research) as a senior research

professor at CERI which is the “Centre de Recherche Internationale”

(International Research Center), SciencesPo (Paris). You have authored, of

course the book, “Karachi: Ordered Disorder and the Struggle for the City” and

this is the book that we will mainly discuss today. However, you also have

written a sequel to this, which is “Gunpoint Capitalism”. Before that, you have also co-edited the book

“Muslims in Indian Cities” with Christophe JAFFRELOT. You have written “Armed

Militias of South Asia and Shared Sacred Sites in South Asia” and there is one

more book that is “Proud to Punish: The Global Landscapes of Rough justice”.

Is this a fair introduction?

Laurent: Yes it is! Thank you.

Anubandh: It is not complete, I am sure but I believe

for the moment this should suffice. I have also one question to you about your

linguistic skills because I know you learnt Urdu. Was it

at INALCO (« Institut National des Langues et Civilisation Orientales

(Paris) ? »)

Laurent: Yes. So, I studied Hindi - Urdu at INALCO for a few years. And then I lived in Delhi for 6 years where in the context also of the collective book you mentioned that I co-edited with Christophe JAFFRELOT on “Muslims in Indian cities”. I tried to better my skills in Urdu at that time in Delhi.

Anubandh: Okay. So, can we also talk in Hindi?

Laurent: Yes. We can!

Anubandh: I in particularly wanted to stress this because in the book you have massively used Urdu. As such, you cited different poems, their importance and we will get to it later. However, language seems quite central to your research, not just as a tool but also to understand the people, the country and the history. Thus, it is really worth mentioning. What I found important in this book is its approach. It is very methodical. It is well researched, it is clinical, it is engrossing, captivating and importantly you have given a conclusion at the end of every chapter. That rather summarizes what we read and I really liked it.

Before we start the interview, I

must tell why this interview is important to me. Because as you can guess, Pakistan

is a taboo word in India. We do not talk much about it and whatever is talked,

it is mostly in the negative Sense. It is often talked through the official

Indian establishment or the state. It is their narrative.

And it kind of prevents us from trying to understand the Pakistani people, the society, their problems. They perhaps have a bit more idea about India through the Indian movies, films and music, than in the other way. But in any case, I think it is quite vital for me that we know each other well. I will give you an instance because being in Paris there is also the luxury of meeting people from different countries. I have some Pakistani friends here. Few months before, I think few years before I was surprised that many of them did not know what was a dosa and an idli! Which is quite a pity because there are some decent Tamil restaurants here (in Paris). What is good also is that in Paris we get some mangoes from not just India but also from Pakistan, which is not possible there (in India)!

Therefore, in this discussion we will try to constantly make some corollaries to India specific references. So that it is easy for them (Indians) to follow. Further, I believe it is important that academic writing comes out of the books and research institutes. And it is made accessible so that lay people can understand and follow it.

Sorry for this long introduction and justification for this interview. This is also because as you confirmed to me, it is for the first time you will be talking about this book to the Indian audience. So, thank you again.

My next question is why this book? And why the idea to study the city of Karachi?

Laurent: Well, when I started working on Karachi in the early 2000s. The city was coming out from an already long sequence of conflicts, of militancy of various kinds, which started really in the mid-1980s. Maybe we will come back to it. In the course of those conflicts Karachi got the reputation which I think was not entirely fair of being one of the most dangerous and most violent cities on earth. At the time when I studied, when I did my research this was clearly not the case. There was a lull in violence and I was concerned about these assumptions making Karachi as it was often nicknamed, “The Beirut of South Asia”. Later on, “The Colombia of South Asia”, etc. What I saw and the more I researched the city, the more I investigated the roots of this violence, its impacts, and its imprints on the social and political fabric in the city. The more it seemed to me that indeed violence was central to the fabric of the city. However, it was also to some extent contained, regulated. This was not a city on the verge of chaos or even if it had at some point, it had been on the brink of a civil war, it never really entirely fell into the abyss. For me, this was the initial enigma to understand actually, why the city was not more violent than it could have been.

Anubandh: I happened to watch an interview that you gave to the Pakistani YouTube channel, “The Pakistan Experience” where you talked about this book. In that interview, you mentioned that you found a bit boring the narrative about the city which concentrated mostly on its Jihadi aspects or of the importance of the army. Perhaps, it (this observation) was not only about the city (Karachi) but in general about Pakistan. You wanted to explore more about the social, cultural, historical and political aspects of the city. You also constantly keep referring in the book to other conflict zones in the world including Brazil, the favelas you talked about, the Colombia case you talked about. You in fact also mentioned about the “Gilets Jaunes”, the “Yellow Vests” manifestations in France. So how do you look at this kind of expansion of the example of Karachi to other places?

Laurent: As you pointed out when I started this research in the early 2000s, indeed Pakistan was old too often and that only increased after the events of 9/11 (11 September 2001) 2001, it was often reduced to, I mean the importance of the army, its collusion with Jihadists, emphasizing Pakistan as a center of international terrorism. In Karachi at least the Jihadists and Islamists, more generally were never a serious political force to reckon with after 9/11 (11 September 2001). They did take a hold in the city. They organized a campaign of militancy that really disrupted the city but they never became a central, major force in political or even in territorial terms in the city. They were just one of the many stakeholders, one of the many parties to the conflict. Thus, what I tried to do was to assess the much larger configuration that was at play. Its historical roots. In addition, what intrigued me was that the most violent actors in the city who are actually not religious organizations but secular forces which at the time incidentally were very much supported by the West! Therefore, there was here an anomaly in comparison with what was assumed the center of conflict in Pakistan.

And on the other part, I mean from its inception this project was comparative. This is the way we understand political science at my institute at CERI in SciencePo. Even when we do case studies we understand these case studies as inherently comparative in the sense that they are inspired by transversal questions, by our readings, by the everyday discussions we have. This is a research institute where all my colleagues work on various areas of the world. Therefore, it is also on an everyday basis we exchange, we influence each other. Thus, from the very beginning and all along its course, all this research on Karachi has been trying to wide catching the singularity of Karachi to make it a case of something much larger.

Anubandh: I guess your work in India must have also helped you in this comparison. By the way, to make a comparison of Karachi with Pakistan, extrapolation of your observations from Karachi to Pakistan, to what extent it would be credible or correct in a way?

Laurent: In a way, Karachi has a specific history in the history of Pakistan. It is a history, which incidentally is very closely linked to India. If we return to the terrible aftermath of partition when hundreds of thousands of so-called Muhajirs; these are migrants who migrated in particular from the United Provinces currently Uttar Pradesh or the Deccan around Hyderabad. The arrival of massive influx of this Urdu speaking population not only created a major urban housing crisis in Karachi for the years to come, way up until the early 1950s, but it also entirely changed the ethnic, cultural, linguistic outlook of the city. From a city which was essentially Sindhi where trade in particular was largely dominated by the Hindu trading elites, almost overnight the outlook of the city dramatically changed. Karachi became an Urdu speaking city. Not only this it had many other communities of which maybe we will talk later but the arrival of this Urdu speaking population with roots in India, which remained very much, attached to its places of origins in India. You mentioned Urdu poetry but the fact for instance that many of the Urdu speaking poets had their “Takhallus” (pen names), which was still, so their pen name still referring to their place of origin like Telavi, Amrohvi etc. It showed also this persisting attachment of the city, of the Urdu speaking population, especially its cultural elites to their homeland, to their place of origin in India. Then the politics of Karachi changed even if it was related to major issues in Pakistan. Federalism, army interventions, etc. It had a peculiar colour linked to those demographic changes.

Anubandh: In fact, when we read your book you also

mentioned that many of the colonies in Karachi, I do not know if that still

exists but they had references to the cities of origin like Delhi Colony,

Bangalore Town, Bihar colony, and others. That is quite interesting. Since we

are talking also about this link with India, could you tell us about the link

between the city of Bombay and Karachi? Are there similarities, differences? We

can also compare Shiv Sena with MQM.

How would you respond to this comparison?

Laurent: Well, clearly. I mean there are two sorts of cousin cities. Delhi and Lahore sharing a political, architectural history, a similar cultural outlook. They have been cities similarly affected by partition. In the same way, there is a form of connivance between Bombay and Karachi. They were parts, administratively under the Raj until the 1930s, as part of the Bombay Presidency. Therefore, there is that already historical administrative Legacy. There was already in the colonial period a circulation of trading elites in particular. Traders, bankers circulated. Some communities like the Memons from Bombay and Kathiawar circulated from the West of India to Karachi, as early as in the 1930s. All the major trading houses in Bombay had often branches in Karachi. Thus, these links were there before partition. However, obviously with the migration from Bombay of the vast majority of the Memon population in particular, these were reinforced. They had their own trading practices that they brought to Karachi. It also changed the outlook of the city. Then the postcolonial history of Karachi, you mentioned Shiv Sena and I mean the parallel is obviously striking. You have a similar brand of ethnic politics, which took a more religious coloration in Bombay than in Karachi. But in many ways the xenophobia, the militancy, the engagement, the rooting in the city of Shiv Sena and the party that came to dominate Karachi's politics from the mid eighties, “The Mohajir Qaumi Movement of the National” Mohajir movements, then renamed as “The Muttahida Qaumi Movement” to “The United National movement” in the late 1990s, had very very strong similarities.

Anubandh: I will now take you back to the question I mentioned in the beginning. It is about the approach of the Anglo-Saxon writers, political commentators on India - Pakistan. If you could distinguish them with the Latin researchers, like you. Because Britain as a colonizer, as an ex-colonizer has a different legacy which France, a background that the French authors do not really share with India. So, do you distinguish, do you find certain subtleties or differences when you look at this research done by the Latin Professors?

Laurent: I do not think I would call them Latin. I do not believe there is a cultural difference. Maybe in Pakistan more than the colonial legacy what was quite important for my research was the fact that I was not American. Which in fact was much more important than the fact that I was not British. In the early 2000, post 9/11 (Septermber 11, 2001) being a foreign scholar in Pakistan, if you were not American or Israeli, you know things could happen to you. Therefore, in a way, even the British legacy would have been something manageable. Nevertheless, the fact of being French made me seem more neutral. I was not directly associated with the US. For instance, the fact that France diplomatically also took a stand against the invasion of Iraq made us seem a bit different and offered some protection, some acceptability. How that affected my perception, the way I conducted research and wrote, that is harder to say. Especially considering that I do not believe in “methodological nationalism”. I do not think there is a French way to engage with the world. In any case, much of our reading, much of our collaborations have been international. There is an internationalism of academia, which does not fit very well with the idea that we operate under national banners.

Anubandh: Yet, I would argue that since you said that in the subcontinent a lot of major writings is done by Indians and Pakistanis, even then, when you read books, like your book and that of Christophe (JAFFRELOT), we see a difference. Which I could highlight as in terms of curiosity, in terms of rigor, in terms of approach… Perhaps, it could also be related to the availability of resources, material and otherwise… Do you agree with this? This difference which is inherent?

Laurent: No. As I said, earlier work for instance on Karachi was published by Nicolas KHAN, by Oskar VERKAAIK. So, Nicolas KHAN is a British anthropologist. Oskar VERKAAIK is a Dutch anthropologist. All this was published in English. There was virtually no French writer. Michel BOIVIN had been contributing some work on Karachi at that time. However, there was very little French scholarship that I could rely on. My major inspirations were foreign scholars who had been writing on the city. It was also work by Pakistani scholars, sometimes teaching abroad, people like Kamran ASDAR ALI, for instance. These people have hugely influenced me. So no, I do not really define myself as a French scholar.

Anubandh: Ok. Fair enough. Just a last question on this topic. I keep asking this question also to Christophe (JAFFRELOT). It is about why we do not see Indians or Pakistanis writing about France, Italy, Germany or other (countries) cities, as extensively as Christophe (JAFFRELOT) has done or you have done? Do you agree with this argument? If yes, what could be the possible reasons?

Laurent: Well again, I think urban studies is a much internationalized discipline. If I look at Karachi and there was really a Dutch Urban School around Den Van Der Lyndan. People around him who were more into urban planning issues, who were doing things very similar to what the Orangi pilot project would do around people like architect Arif HASSAN. Therefore, in Karachi there has been so much scholarship on the urban (studies) around people like Arif HASSAN. We also have the Karachi Urban Lab. There is a glorious tradition which was a bit different from what I was doing because very often these were more technical issues, which were more committed to development, planning. However, I could rely on that. Thus, again, on the contrary I think the French were quite late comers to that scholarship.

Anubandh: Okay. However, frankly I would love to read writings by Indian and Pakistani authors on France and other countries… That would be equally interesting. Now moving on…

Laurent: But just on that question. I do not think that the problem is a lack of ambition on their part. It is a lack of finances, it is a lack of facilities. These are difficulties of accessing, of being granted visas. The fact that European universities were until recently not particularly welcoming. Most of the teaching was in French. Therefore, there are structural reasons. I do not think it is out of a lack of interest but it is because of structural obstacles. Many of which come from European governments.

Anubandh: We indeed mentioned the lack of resources could be a possible reason and you confirm that.

Nevertheless, I think it needs to be told that your book is published in French as well as in English. So, two languages.

Now moving. Since we mentioned

about the importance of poetry in the Karachi narrative, I have a few examples

from your book. I will cite them and I will then ask you to respond to it. You

mentioned that poetry was central to this Urdu dominated city. You also gave an

example of when the refugees came from India, often in their applications they

would cite a Mirza GALIB's poem or other poetry, poetic expressions. You also

related it with the self-expressionist movements of the 1930s. And how that

could have been one influence. You as well talked about poetry as being an

intoxicant. For example, you said, ”the poetry discussed here is therefore

irreducible to political imagery or to the radical alibi of an otherwise

opportunist party (which is MQM). It is instead a form of politics by itself where

the intoxicating power of words meets the equally mesmerizing beauty of war”. I

think this summarizes well your argument.

However, I will mention two

other aspects and then I will stop and invite your comment.

You identified two forms of politics that made use of the poetry. Regarding the politics by MQM, there is one phrase “salvation of the Muhajir Nation”. You say, “In a more complex way it points at the MQM's simultaneous practice of two seemingly opposite forms of politics. One existential, devoted to the salvation of the Muhajir nation through an endless fight of epic proportions against tyranny”. While the second one is about the “restoration of Muhajir rights and one more earthly centered on the restoration of Muhajir rights”.

Laurent: Yes. This is in general comment on the use of poetry in the politics of Karachi. What I tried to suggest is that the place of poetry in everyday life, in everyday politics in Pakistan has been absolutely central. Obviously it has lost a bit of its appeal over the past decades. You mentioned these applications where refugees would add a few couplets by Mirza GALIB in order to impress and press their case. I am not sure that this is something that people would do today with the administration. It is also the high culture, the very persianized version of Urdu that maybe Urdu speakers would be familiar with. However, it is in the middle and upper classes and castes in the early 1950s where it has gradually disappeared. At the same time poetry remains very much part of the everyday language of politics. In particular of the language of mobilization and contestation. During TV discussions, during TV shows, you will find media personalities, politicians reading couplets of (Muhammed) IQBAL, of (Mirza) GALIB, of the more transgressive, oppositional poets like (Faiz Ahmed) FAIZ, Ahmed FARAZ, Habib JALIB which remain so central to the language of protest in Pakistan. Or they will just recite couplets of their own. But you will also find in everyday life people quoting poetry here and there. There are indeed two major ways to quote poetry in these everyday Interactions. One is to invoke the theme of resistance martyrdom. The theme of Karbala which remains so central to the imagination of politics and especially protest politics. This is what the MQM had done. It was constantly playing with this theme of Karbala, to mobilize its people and give an epic dimension to its struggle. Then there is a more mundane way which is indeed to press grievances, to reclaim, to claim rights which is also a way to give a certain weight to these claim making enterprises.

Anubandh: You mentioned Habib JALIB. There is his famous poem “Dastoor” and there is also the poem by Faiz Ahmed FAIZ, “Ham Dekhenge”. These two poems were widely recited during the Anti Citizenship (Anti CAA) law protests in India few years before. There is also this book by Fatima BHUTTO, “Songs of Blood and Sword” which is quite famous in India. We can note as well its poetic title, which is a confirmation of what you just said. Further, in your book you have cited several small poems, for example by poets like Rais AMROHVI, Zeeshan SAHIL. Would you mind to recite a small poem if you remember?

Laurent: No, I do not remember. I will spare your viewers. I do not have any couplets right now. But if your viewers are interested, I would really encourage them in particular to discover the poetry of Zeeshan SAHIL. He is very important, original, avant-garde poet of the mid 1990s in Karachi who died prematurely in his prime. He unlike the greater poets, the more well-known poets that you mentioned was really a chronicler of everyday life. In a book he devoted to Karachi itself, in the midst of the conflict in the mid 1990s, it really provided a chronicle of everyday turmoil in Karachi like no one, no other writer did.

Anubandh: I would still insist to read, recite a small

couplet that you mentioned in the book by Rais AMROHVI. Please forgive me for

my potentially bad pronunciation of Urdu but it goes like this,

“iss shahar me ashia hai anka,

dil sakhth yaha ulajh raha hai,

pagdi ki taaleb hai ghar ke

badle,

pagdi me makaan ulajh raha hai »,

which means,

“there is no shelter in the city

of Karachi,

the heart is in great turmoil,

when our immediate concern is to

preserve our dignity

how will we manage to find a

home?”

Thank you. Now begins some

serious, complex work. I propose to share with the audience some acronyms from

the book, as there are many. I think it is important that the audience gets a

chance to have a glimpse at it.

There are also some interesting maps, charts and tables that you have included in this book. I propose to share them one by one. There are two maps of the city of Karachi. I took these maps from the Reddit website so that back in India people could have an idea about the ethnic composition of Pakistan. Do you agree with this map?

Laurent: Yes, broadly.

Anubandh: Ok.

Here, we should broadly identify

five nationalities, ethnic nationalities in Pakistan. One of them is from Sindh,

in which you have Karachi with a huge population of Muhajirs. Then, you have

Baluchistan so Baluch from there. You have of course Punjabis, then Pashtuns and

then there are other embedded sects there.

This second map is a more detailed view of the ethnic composition.

Then we have the city map of

Karachi. I think it could also be interesting for people back in India to have

a look at the city of Karachi. You have mentioned in it the industrial ports,

the industrial areas and other places. If you have any memories, any comments,

you are welcome to comment.

Laurent: As you can see, Karachi really is an urban sprawl. The city is historically developed along the bay, around the harbor. It was a major entrepôt city until the Independence. It had very little, almost no industries until 1947. All these industrial areas that we see which came to redefine also the outlook and the economic importance of Karachi were all developed in the peripheries of the city after partition.

Anubandh: Okay. Thank you.

You mentioned about the industrial areas. This is in fact the central theme of your next book (“Gunpoint Capitalism”). Rather, this book is already published and we will perhaps get a chance to talk about it next time.

Further, we could talk about the

different languages of Karachi. This will as well provide a glimpse about the

ethnic composition of Karachi.

You have shown here how the proportion of the Urdu speaking Muhajirs is reducing while those of Punjabis, Pashtuns and Sindhis is increasing, over the years.

I have also the share of

population, the share of migrants into the population of Karachi. We can see

here that the population has increased quite a lot. You have almost two millions

of migrants in 1998.

There is also this spike in the

influx of migration after 1947, it is at 161%. Earlier, there was one in 1861

as well and then again in 2011.

Next, a very sordid picture. It

is about the killings in Karachi. In 1995 we have a huge spike. Then again in

2013. I am sure things have changed since because your book was published in

2014. Thus, this data is restricted to until 2013.

Moving on, could you please tell us about the Muhajirs? The etymological explanation of this word? The fact that they were urban elites from India whose language was chosen as an official language of Pakistan. Thus, in a way they had an upper hand in terms of getting access to education and jobs. Yet there was a feeling of being discriminated, which perhaps was gradual. It is this that led to the Muhajir nationalism. So, could you please tell us about this Muhajir movement and its historical background?

Laurent: Yes, the Urdu speakers who migrated to Pakistan after partition were labelled “Muhajirs” which initially was an appreciative term. Literally, it means migrants, refugees. However, it refers to a glorious episode of Islamic history where when the prophet moved from Mecca to Medina, and thus it was at the time of the Hijrah. The Muhajirs are those who have done the Hijrah in the glorious company of the Prophet. Therefore, that term defines reference to that History. It defines also a relation of interdependence and hospitality between the Muhajirs, the migrants and the Ansars or those who welcome them, grant them hospitality. Therefore, the idea for the first Pakistani political authorities and administrative authorities who used the term was also to grant a veneer of legitimacy. The religious legitimacy in particular to that relationship. Especially because very early on some tensions emerged between the indigenous population of West Pakistan and this massive influx of migrants from India. There were some tensions from the very beginning around housing, jobs, around the perception that in fact this population benefited from or got some preference from the Pakistani state. Then things started to change already from the late fifties when the capital was shifted from Karachi to Rawalpindi and then to Islamabad in the sixties. At that time, the fact that the capital, the political capital was in Karachi made it easier for Muhajirs not only in the bureaucracy but also in the economy, for all businessmen to have access to political power. It is really through that entrenchment of economic, political, administrative, bureaucratic power that the Muhajirs came to dominate the early years of Pakistan. That started changing from the 1950s. Then from the late 1960s, early 1970s we see a rise of Sindhi nationalism in Sindh itself. Especially under the leadership of Zulfikar Ali BHUTTO. After the arrival to power of BHUTTO we see a gradual flaring up of tensions. The first linguistic riots between Sindhis and Muhajirs happened in Karachi in 1972. Gradually BHUTTO introduced also quotas in the bureaucracy. Opening the bureaucracy up, making it more representative and in particular to its core constituency which was made of Sindhis. Therefore, this really fuelled the sentiment among Urdu speakers that they were being discriminated against.

However, let us emphasize one thing. Mohajirs were not all elite. The vast majority of Muhajirs were actually artisans, working class people. They also worked at that time in factories, in small workshops. Thus, all these were not elite. It is also that lower middle class that became the backbone of Muhajir nationalism. From the late 1970s onwards a group initially of student activists re-appropriated the term “Muhajir” which by then had become a derogative. They made it a source of pride and a source of unity to mobilize against their perceived enemies and to claim new rights towards the state.

Anubandh: You also talked about the MQM. You used the terms “King Maker” and the “King Breaker” of the city. You as well talked about its capacity to order the disorder. With the two meanings of the word. One it is to order the disorder but also about, its capacity to tame it at will. We also witnessed that MQM changed its name. It became “Muttahida Quami Movement”. Thus, that was its capacity to transform. You highlighted that it could adapt to the changing situations. It was also because it wanted to widen its spectrum. Not to keep it limited only to Muhajirs. Therefore, how would you comment on the MQM's capacity to transform?

Laurent: As I briefly mentioned, initially the Muhajir nationalism really crystallized around student activists at the university of Karachi in the late 1970s when the founder of MQM Altaf HUSSAIN was studying. He started this small group called the “All Pakistan Muhajir Student Organization”, the “APMSO” which at that time did not have much influence. It did not really pick up. For one reason in particular because he did not have enough weapons. You must know that these are the late 1970s, early 1980s. Karachi is flooded with weapons which have been allegedly lost in transit going to Afghan Mujahideen. Therefore, every student organization in the city which competes for control of the campuses but also of certain turfs across the city, all of them are armed. At least every student group that has some stakes in the city is heavily armed with Kalashnikovs. Sometimes even with heavier weapons. The MQM is a latecomer at that time. It is under the protection of other organizations. It will be kicked out of the campus and it will really return later. It is such a failure that Altaf HUSSAIN himself moves to the US, becomes allegedly a taxi driver in Chicago for a while. So, all seems lost for Muhajir nationalism and then the situation changes. He returns to Pakistan in the mid-1980s. Then allegedly with the support of the so-called deep state and the dictatorship of General Zia (UL HAQ), in order to counter both the Islamists of the Jamaat e Islami and Sindhi nationalism, allegedly receives support.

However, this is not the only explanation for the rise of this formidable force. It is also that the city itself has changed. New conflicts have emerged. The Afghan war has not only brought weapons, it has brought drugs, money, a new Pashtun migration, criminal organizations that are emerging. The MQM will reinvent Mohajir nationalism as a form of muscular nationalism that will give both pride and weapons to the majority population. It is gradually from the mid-1980s onwards that it will become a formidable force, which at the same time draws its power from the urns. MQM wins every elections that it contests. Whether local, regional, national. From the mid-1980s onwards. At the same time as it plays the card of democracy and legalism, it also plays the card of mayhem. Regularly it calls “Hartal” (strike). Therefore, these are days of general strike. It can close the city at will. Only one call from Altaf HUSSAIN and the city will entirely close down. This will be followed by ethnic riots, which are engineered by the MQM. It has this capacity to order violence. It can also call the end of violence. It is this capacity to order disorder and to control it at will, which makes it so powerful and unpredictable, at the same time. However, this strategy also shows its limits because electorally the party cannot expand beyond its two major strongholds in Sindh. In urban Sindh which are Karachi and Hyderabad. Then from the late nineties, after a long sequence of heavy repression from the state, it tries to expand its electoral base beyond the Muhajir community. This will never really succeed.

Anubandh: Yes and there is a funny mention in the book where you amusingly say that Altaf HUSSAIN was also-called “Hartal HUSSAIN” because of his capacity to order “Hartals” (Strikes) at will.

One question regarding the reference you made about the influx of weapons. As one is tempted to compare India with Pakistan and ask why there is such ubiquitous presence and easy access to arms in Pakistan. Can we, at least to some extent hold responsible United States for this situation in the 1980s or 1970s, during the war in Afghanistan?

Laurent: Yes, it is the US, it is the Saudis, it is all the western capitalist block. It is this that supports the Afghan mujahideen who are branded as heroes at that time. It is also the so-called deep state, the “Badi Sarkar” (The Big Government) as they call it in Pakistan. At that time General Zia UL HAQ is in Power. At the helm of its power the Inter Services Intelligence, the ISI orchestrates this transport of weapons with the CIA (Central Intelligence Agency). Many of these weapons, huge loads of weapons will be lost in transit on the way. These will be hijacked either by Pakistani agencies or by several intermediaries along the way. Karachi with its ports being the major international port of Pakistan many of these weapons consignments arrive through Karachi's port and will be hijacked from the port of Karachi itself.

Anubandh: Just a few more words about Altaf HUSSAIN. He is in London since 1992, right? You give instances in the book that even from there he very closely manages the happenings in the city. There is an instance where you were interviewing someone and there was a death of a person in the city. At that moment, there was a call to the unit head of MQM from London even before the news had spread in the city. This kind of gives an example of how deep is this influence. However, I was also looking at the internet and there are some very recent proclamations and demands by Altaf HUSSAIN. One of them was, surprising to me was a demand for the “Sindhu Desh” (Country for the Sindhis) where he wanted a separate country for the Muhajirs plus the Sindhis. How do you explain this demand, which enlarges the scope of this new nation and accommodates Sindhis in it?

Laurent: This has been an old call from sections of the Mohajir nationalist movement, which have always maintained an ambivalent relationship with Sindhi nationalism. In a way, the Muhajirs live in Sindh. Karachi, Hyderabad are in the Sindh province. Very few Muhajirs speak Sindhi until now. However, there have been repeated attempts to build the coalition with Sindhi nationalist elements. As I briefly mentioned earlier, in the late 1970s, early 1980s when Altaf HUSSAIN and his colleagues were only students at the University of Karachi and they had no weapons, it is initially through Sindhi nationalists that they got their first weapons. It is thanks to them that they got their first training. Because at the time Sindhi Nationalists already had a long, strong experience in terms of weapons handling. Thus, there was this attempt to build a form of Sindhi nationalism that would accommodate both Sindhi speaking and Urdu speaking nationalism. Therefore, this project of Sindhudesh has been off and on, been agitated by MQM. How genuine was it? I do not think it was very serious on the part of MQM. It was more a matter of rhetoric. Today, even more than ever, especially considering that Altaf HUSSAIN has been very much alienated from Muhajirs, he has lost much of his appeal to Urdu speaking Karachiites. In any case, the MQM Pakistan has been very much marginalized in Pakistan politics for the past decade or so.

Anubandh: Okay. Fair enough. Moving on, your book has some dedicated chapters and I propose to at least read the titles since we will not get time to go and visit each of them. I will jump to the second chapter. It is about the student movements that we discussed and how they were linked or they transformed themselves into political parties. We can give examples of the APMSO (All Pakistan Muttahidda Students Organization) for the MQM, PSF (Peoples Student Federation) initially for PPP party.

Then the chapter is about

“Muhajirs have arrived” and we have talked about it. However, the two important

chapters of which we have not talked much about and I would like us to comment

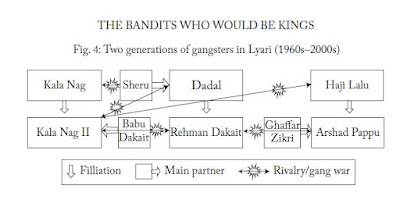

on it. It is about the bandits of the Lyari. Lyari is a neighborhood of the

city of Karachi. Then the last chapter is about the jihad. The rise of jihad in

Karachi. I found it very interesting this graph that you have shared in the

book. I will share it with the audience. It is about the different groups,

warring groups and gangs of Karachi. Could you please tell us a bit about this

underworld of Karachi, which still influences the politics there?

Laurent: Yes. It is a complex topic. I am seeing this graph after many years. I now realize that visually, I could have probably done better. However, the point was really to show that there is a long history of gang rivalry in that particular neighborhood. You need to say a word here about that neighborhood Lyari that is a really poor working class neighborhood. It is part of the old indigenous city right next to the port. It has today become a degraded inner city. It is one of the poorest, most neglected areas of Karachi. For a while, it also became its most violent, graded place. The location of the neighborhood is important to understand how certain forms of criminality developed there from the 1950s and 1960s onwards. Because this was a place of contraband, which arrived from the ports in particular, and it is adjacent to the wholesale markets of the city where parts of these contraband goods would be sold. Then when Zulfikar Ali BHUTTO closed down, when alcohol was banned when gambling was banned, Lyari also became a place famous for its illicit gambling dens and illicit places selling alcohol. At that time, this was still petty criminality. When there were criminal rivalries, they were essentially settled with knives. It is really again with the impact of the Afghan jihad, with the fact that so many weapons and heavy weapons arrived in the city that these criminal rivalries really escalated into gang wars. The state played a role in it. Very often these gang wars, we will see also proxy wars between political rivals. The MQM supported one group against another group that was supported by the PPP. The army itself allegedly supported certain groups to counter the rise of Baloch nationalism in the neighbourhood. Therefore, this made these gang rivalries extremely complex and deadly.

Anubandh: Yes. I must tell the audience that when I read the book I realised that people in India are generally very impressed with, impressed also in a negative sense about the underworld of Mumbai. When I read things about Karachi, I believe it is a very benign version of underworld what we had or have in Bombay or Mumbai.

One more aspect about Lyari. And you would confirm if it is true. It is apparently the only bastion of the PPP in that city and the rest is to MQM. Benazir BHUTTO and others (BHUTTO family members) even from Zulfikar Ali BHUTTO, they had a massive following there. That could be perhaps compared to the Bellary for Congress in Karnataka or more pertinently to Amethi or Raibareli in Uttar Pradesh.

Now the last, important chapter. It is about how in recent times the Pakistan Taliban has made some serious incursions into Karachi. It has in a way beaten MQM at its own game. How would you explain that challenge to MQM and what is the situation today, post 2014?

Laurent: Well, Karachi is, even if it was in terms of demographic majority an Urdu speaking city until recently, it is also the largest Pashtun city in the world. It has had a very significant Pashtun migration from the Northwest of Pakistan, from the 1960s onwards. This migration only increased with the conflict in the Northwest after 9/11. After repeated, brutal military operations led hundreds of thousands of Pashtuns to move out of the Northwest and become IDPs, Internally Displaced Persons, in particular in Karachi. Therefore, a whole section of the city, especially in the north, northwest of the city but also some pockets in the southeast have become Pashto speaking majority areas. Moreover, these areas provided a fertile ground for various Jihadist groups, especially for the Pakistani Taliban, or the so-called “Tehrik e Taliban Pakistan”, after its creation in 2007. Some Taliban fighters would take shelter in the city, initially using their relation, using the ethnic composition of these neighborhoods to hide and regain some forces before going back to the major battlefields of the Northwest. Then gradually the Pakistani Taliban rather consolidated its basses from the late 2010. Then it started also competing against the MQM for hegemony over the city and started launching attacks against MQM.

Anubandh: Thanks. Time is short but I still wish that we give a glimpse to the audience about the different political alliances, which the MQM made. These are very interesting. I made a small compilation and you will tell me if it is correct. It is about the different major political alliances, which the MQM made right since 1988. It is an example of outright opportunism or pragmatism at best.

The first one is in 1988. MQM makes an alliance that is called “Karachi

Accord” with Benazir. In 1989, we have: MQM supported the new confidence motion

led by Nawaz SHARIF against Benazir government and which failed. In 1990, you

have Benazir BHUTTO government dissolved by President Ghulam Ishaq KHAN and the

reasons given were worsening law and order situation in Karachi and in

Hyderabad. Later in 1990, you have MQM, which makes an alliance now with Nawaz

SHARIF PML. In 1992, you have Sindh Chief of Army Staff, Asif NAWAZ who sent

army (in Karachi) without Nawaz's knowledge and approval to crack down on the

MQM. This was partly due to worsening law and order in Karachi. However, PPP this

time was reluctant to ally with the MQM. MQM boycotted the elections. December 1994,

you have withdrawal of army from Karachi. That was the famous “Clean Up” operation

against MQM and which led to escalation of violence. Year 1995 is the most

violent post-colonial year of Karachi. In 1995, you have crackdown against MQM by

Home Minister of Benazir General Nasirullah BABAR. Massive encounters that took

place during this period. Murtaza BHUTTO (Benazir BHUTTO’s brother) and you

mentioned him as someone being “hot tempered” was murdered. Rumour attributes

it to close aides of Benazir BHUTTO. This was followed by the dismissal of

Benazir government by President Farooq LEGHARI. Main accusations were that

acquisition by Benazir of a sumptuous villa in Surrey in UK, political

manipulations in Punjab, possible involvement in the murder of Murtaza, increase

in extrajudicial killings by Police and Rangers in Pakistan. Later, In 1997 PML

was in alliance with MQM. They formed a government. Then once again, MQM

withdrew support to the provincial government in Sindh. Further, governor Hakim

SAID was killed by MQM in September 1998. MQM withdrew support to SHARIF. SHARIF

dissolved assembly and proclaimed state emergency. Year 2000, law and order

improved, as claimed by the newspaper Herald and it called the city, “The city

of Life, Karachi”. Then there was a conflict between MQM and ANP. 2002 - 2008

years, the Musharraf years are meant good years for the MQM. There is an alliance

between them. Post Musharraf in 2008, MQM made an alliance with the PPP. MQM

withdrew its support in December 2010, then in June 2011 and once again in

February 2013. Year 2013 was the most violent year ever for Karachi.

Sorry for this long summary but I think it was important. Do you have

any general comments about MQM, as being a very mercurial, untrustworthy partner

and yet pragmatic and opportunistic in a way?

Laurent: Yes. What is

fascinating about this party, in its glory years that you presented, it is how

it acted both as an oppositional movement. It used the word “Tehrik”. A “movement”

which has this connotation of

subversion, of social mobilization, of being a transgressive force and at the

same time a political party engaging with what is referred to pejoratively in

Pakistan as “Partybazi”. Thus, really the petty politics. It is this tension

that never entirely leaves most militant parties once they get to power and

tend to play the game, become pragmatic, opportunistic and cynical. The MQM

remains, part of the MQM remained true to its agitational politics of its

student years. That is, you described it as a mercurial force, this is

precisely its dual legacy that it never entirely broke away from which made it

so particular.

Nevertheless, all this is now a thing of the past and the MQM has really been cut down to size. After 2015 when there was another massive paramilitary crackdown on the party. This time, the party never regained power after this.

Anubandh: Okay. Thank you. We are now reaching the end of this interview. However, I still have few last questions. One is about the mention that you made in the book. It could make a ring in the ears of the Indians. It is about the failure of the “Two Nation Theory”. You cited one example or one argument given by MQM, saying that the fact that there were four nationalities; Pashtun, Punjabi, Baluch and Sindhi other than the Muhajir, in a way it was a proof of failure of the “Two Nation Theory”.

I would add perhaps two more arguments before I request your comment. One would be the fact that more Muslims in 1947 decided to stay back in India than those who chose to come to Pakistan. Second would be also the 1971 separation of Bangladesh. Does this make the count three? Are there more to this?

Laurent: Okay. I think you cannot take the words of MQM for granted. When they criticized the “Two Nation Theory” this was part of their theory, political rhetoric and provoking the Pakistani state. Besides, this was a rhetoric, which has not really aged well in Pakistan. Today many people in Pakistan, including in the MQM's ranks would say that the fate of Muslims in India validates the “Two Nation Theory” project. In addition, that hopefully the Pakistani state was created to provide shelter to at least a section of the Indian Muslims. Therefore the recent developments, since the arrival to power of Narendra MODI has rather rejuvenated the “Two Nation Theory”. The Pakistani project and in that sense after decades of disillusion in a way, the Pakistan nationalism has grown larger and stronger. Very much thanks to MODI's government.

Anubandh: I asked this question also to Christophe (JAFFRELOT)

in one of the recent interviews I had

with him. I asked him, has the

politics of Narendra MODI proved the “Two Nation Theory” of JINNAH right?

How would you respond to this?

Laurent: No, I mean, it is not my role to say who was right, who was wrong. I am a social scientist. All I am interested in is how the people I study, the people I work with perceive it. What I see is among many of the Pakistanis I interact with, maybe not certainly in Balochistan right now. But at least outside the most contested parts of the country where Pakistani nationalism is the most contested even if there is despair with the economic crisis, there is at least a sense that Pakistan provided a roof and a certain limited, however imperfect protection to Muslims of the subcontinent.

Anubandh: If you are interested in Christophe's answer….well, it is a speculative one. He says that this claim is counterfactual because the elites, the Muslim elites in India decided to go to Pakistan and not stay back. Which means they left the Muslims at the mercy of the Hindu dominance. Well, that could be possibly one reason.

Now, I really wish to summarize your book and I have made a small chart, because the basic question, the important one that remains is why Karachi is an ordered disorder?

And as a summary you asked two

questions in the book and one is:

How did armed conflicts become endemic in the city since mid-1980s?

Second question:

What spared Karachi a general conflagration despite repeated sequences of violent escalation accompanied by ethnic, political and more recently religious polarization?

And you kind of give four answers to these questions.

The first one is, “MQM's capacity to order disorder that is a capacity to unleash but also to tame civil strife as well”.

Second: “Karachi has been characterized since the mid-1980s by the inability of any actor to exert a complete domination over local politics and monopolize the means of coercion and the ability of one actor, the MQM to dominate the game nonetheless.”

Third: “The city's armed conflicts have been fuelled but also moderated by a genuine, yet unconsolidated democratic context which saw the development in the shadow of military interventions of an armed consociationalism, regulating the tense relations between ethnic based and partly militarized political parties”.

And the very last, fourth and

the important one. It is this one, which is very difficult perhaps for the

Indian audience to understand. It is about:

“The role of state agencies and in particular of the army whose repeated attempts to restore order through performances of legitimate violence through the outsourcing of illegitimate violence and through a politics of patronage has had mitigated effects both nurturing and moderating violent conflicts in the city.”

Yes, Laurent, how

would you respond to these conclusions? Are they the same after 10 more years

that you wrote the book?

Laurent: No, as I said the situation has dramatically changed after 2015. Because factor four, the role of state agencies became prominent over all of other factors. Suddenly, the army did something that it had not done before which was to demilitarize everyone. Until then the army had acted as a partial empire, which was arbitrating the conflicts of a city in a very partial way. This time it went hard against everyone. It went the hardest against the MQM but it also went hard against the gangsters of Lyari, against Pashtun nationalists, against the Jihadists. So much so that largely Karachi has become demilitarized except as far as law enforcement agencies are concerned. It has become heavily policed not only by the police but also by the paramilitary rangers, by private security, by various forms, many of the former musclemen of previous conflicts have become security suppliers. For instance, for industrialists, for traders. There is still much muscle power at work but the time of militarized politics is over. Clearly, there are signs that this is not going to resume. It has now been 10 years that there is, on the surface, peace in Karachi. Occasionally there is a bomb attack but nothing compared the gun battles of yesteryear, of the time when political parties could have gun battles in the streets for several days. This is over. Moreover, I think this is not here to stay. It is a new form of Karachi, new forms of violence which are the ones that I describe in the following book (“Gunpoint Capitalism”) which are more linked to a new brand of capitalism which are emerging. These are either linked to industrial capitalism but also increasingly to real estate. There are formidable forces that are emerging around real estate actors who once again working in collusion with the army which are now the structural violent forces in the city. Therefore, in that sense that peace is only superficial. Behind the surface social conflicts are still brewing but they are less visible.

Anubandh: Thank you. I really wish that I get a chance to talk to you about the next book which is “Gunpoint Capitalism”. We also briefly discussed the possibilities to see if it is translated into different Indian languages as well. So, let us see how we go.

I have admired your book and I really mean it. It is really an immersion into Karachi and Pakistan and it gives me even more reasons to visit Karachi and Pakistan. However, I also have a small critique about your book and I hope you do not mind it. It is about the language of the book that I found was very heavy, complex. Perhaps, it is also the subject which is complex. Do you have a small comment on that?

Laurent: It is an academic book. I mean, as much as I enjoy discussing with you, with journalists, with everyone, the core of what we do is scholarship. Therefore, it is written in a certain way essentially for our peers. I think the second book is a bit maybe different and it has more narrative elements to it. At the same time, I had a rather large circulation in Karachi, which rather surprised me. Because it has not been written to reach a large audience. It is written essentially as an academic book and I have been delighted to see that it found an audience well beyond academia in Karachi. I can only hope in India as well.

Anubandh: I am not surprised at all because it is a very engrossing and enchanting book, I must say. I have a very last question now and which is; when one reads your book one discovers the huge scale and the extent of violence in Karachi and in Pakistan. It is very hard to even visualize, to imagine. What effect this prolonged exposure to violence has on the population of Karachi, on the population of Pakistan? Also on researchers like you? Since you have covered the city and observed it for the last more than 25 years.

Laurent: Well, I will be brief because this is a large question. Karachiites have learnt to deal with violence. They have learnt to engage with a form of normality of the abnormal. On the surface, it could feel that they get on with their lives. This is the case of any population in the context of conflict. Life goes on to some extent in a bizarre and uncertain, unpredictable kind of way. Today, most Karachiites do not want the violence. They want to forget this troubled past. They really do not want to revisit this. They want to shift to something else. As far as I am concerned, I had to learn the rules of getting by as well. I did not expose myself unnecessarily. If you look for trouble, you could always find it. Nevertheless, if you tried to respect some of the rules to engage with the people, not to act in a brazen kind of way like some foreign journalists. The kind who would be trying to look for the spectacular, trying to meet dangerous people, at dangerous times, in dangerous places, obviously there would be a sanction. In my case, part of my investigation was also to learn through the people. I avoided putting people I interacted with at risk. I do not think my own safety was my only concern. My major concern, it should be the primary concern of any foreign scholar or journalist which is not to put your local respondents, your local friends, your local informants at risk. This is the kind of thing that we are also teaching our students, which is the basic of ethical work in such conflict zones.

Anubandh: Yes. I think if there is any or only region in India that could be compared to Karachi or to Pakistan for this violence, I would say it is none other than Kashmir. Well, Laurent GAYER, a big thank you for accepting to talk to me, for talking to the Indian audience and giving us such a deep insight into Karachi and Pakistan at large. I look forward that your books are read not just in Pakistan but also in India and in France and everywhere. Thank you again.

Laurent: Thank you and thank you very much.

Anubandh: Bye, bye.

Laurent GAYER

His most recent work focuses on the relationship between capital and coercion in South Asia, as well as on the global landscapes of vigilantism and rough justice more generally. He is the author of Karachi: Ordered Disorder and the Struggle for the City (Hurst, 2014) and, with Gilles Favarel-Garrigues, of Fiers de punir. Le monde des justiciers hors-la-loi (Proud to Punish: The Global Landscape of Rough Justice, Seuil, 2021). He is currently finishing a new book, Le capitalisme à main armée. Défendre l'ordre patronal dans un atelier du monde (Strong-arm Capitalism: Enforcing Corporate Order in Karachi, forthcoming with CNRS Éditions).

In addition to his research

activities, he teaches in the Master's program in political science at Sciences

Po, supervises doctoral students, and participates in the editorial boards of

the journals Politix, Critique internationale, and Contemporary South Asia. At

CERI, he is one of the coordinators of the research seminar “Travail de

l'ordre, police et organisations répressives” (The Work of Law Enforcement,

Police, and Repressive Organisations, TOPOR), which focuses on the contemporary

transformations of policing and the lived experiences of security.

Anubandh KATÉ is a Paris based engineer and co-founder of

the association, “Les Forums France Inde”.

No comments:

Post a Comment